The modern version of Santa Claus as we know him can largely be attributed to Coca Cola’s marketing executives. But where does this strange legend of a ruddy faced merry soul and his flying reindeer really come from?

The figure of Father Christmas evolved out of centuries of pagan traditions, whose elements were first officially cobbled together in the poem “Twas The Night Before Christmas” or “A Visit from Saint Nicholas” in the 1820s by author and professor Clement Clark Moore of Albany, New York. Although Christmas is a Christian holiday, most of the symbols and icons we associate with Christmas celebrations are actually derived from the shamanistic traditions of the tribal peoples of pre-Christian Northern Europe. (The word ‘shaman’ comes from Siberian Tungus word ‘Saman’, the name they give their spiritual healers.)

The Mushroom

But first we need to introduce a new character into our Christmas tale, the amanita muscaria mushroom, otherwise known as ‘fly agaric’. The amanita muscaria often seen illustrated in magical fairytales, children’s storybooks, cartoons and of course, Christmas cards and ornaments. The little red and white mushroom or ‘toadstool’ has gained celebrity status over the years for good reason (little known that reason may be). When consumed, it evokes an intense psychedelic experience. Fly agaric is one of the most potent psychedelic mushrooms on the planet, containing the active ingredient muscimol.

Eating the amanita causes visions and altered states, which have been used by tribal peoples to gain insight and transcendental experiences. The hallucinations often include sensations of size distortion and flying. One of the side effects of eating amanita muscaria is that one’s skin and facial features take on a flushed, ruddy glow (sound familiar?). Those who indulge in the magic fungus tend towards states of euphoric laughter. “Ho, ho, ho!”

Origin of the Phrase, “To Get Pissed”

The active ingredients of amanita muscaria are not metabolized by the body, and therefore remain active in urine. In fact, it is safer to drink the urine of one who has consumed the mushroom than to eat the mushroom directly, as many of the mushroom’s toxic compounds are processed and eliminated on the first pass through the body.

It was common practice among some peoples to recycle the potent effects of the mushroom by drinking each other’s urine. The mushroom’s ingredients can remain potent even after six passes through the human body. Some scholars argue that this is the origin of the phrase “to get pissed,” as this urine-drinking activity preceded alcohol by thousands of years. (For those not familiar with the expression, “getting pissed” is English slang for getting drunk.)

Someone who had eaten fly agaric may drink their own urine to prolong the state of hallucination, or offer it to others as a treat. Drinking the urine of one intoxicated by fly agaric has only a slightly less intoxicating effect than eating the fungus itself. Filip Johann von Strahlenberg, a Swedish prisoner of war in the early eighteenth century, reported seeing Koryak tribespeople outside huts where mushroom sessions were taking place, waiting for people to come out and urinate. When they did, the fresh piss was collected in wooden bowls and greedily gulped down. This method of ingestion was much less likely to cause the vomiting often associated with eating the mushroom itself.

How did ancient peoples gain this knowledge? Why, from the reindeer of course.

The Reindeer

There are many indigenous peoples who used the amanita muscaria as their sacrament. Best documented are the Sami (Lapps) of northern Finland, Sweden, Norway and Russia and the Tungusic and Koryak peoples of Siberia. All of these groups live in the Arctic Circle and are traditionally reindeer herders.

Reindeer were sacred to these semi-nomadic peoples, as they were a source of food, shelter, clothing and other necessities. As it happens, the reindeer have a particular fondness for amanita muscaria, even seeking them out from underneath the snow. When they eat the mushrooms they become stupefied, staggering and prancing around while under the influence.

Reindeer also enjoy the urine of a human who has consumed the mushroom. Reindeer will seek out human urine to drink, and some tribesmen carry sealskin containers of their own collected piss, which they use to attract stray reindeer back into the herd.

When Georg Steller, and explorer, visited Kamchatka in 1739 he noted that reindeer were sometimes intoxicated. The Koryak people sometimes tie up the animals until their condition subsides and then kill them. All who eat the flesh become intoxicated. Jonathan Ott, an American author, suggested in 1976 that use of the fly agaric in the midwinter festivals of deepest Siberia may have inspired some of the imagery of Santa Claus.

The Yurt

Some of these peoples lived in dwellings made of birch and reindeer hide, called “yurts.” Somewhat similar to a tee-pee, the yurt’s central smoke-hole (supported by a birch pole) can also be used as an entrance. The shamans of Siberia were responsible for bringing the mushrooms they collected from under the sacred evergreen trees to the houses of the the people on the winter solstice (a few days before our modern celebration of Christmas on December 25th). Sometimes dressing in the colors of the mushroom (red with white trim) and carrying a huge bag full of mushrooms that were picked and dried during the previous season, the shaman would go door to door to give the community the mushroom experience.

If the main door to the houses were snowed over (which they often were during the winter time), the shaman would enter the houses through the smoke-hole in the roof or the chimney. Climbing down the chimney-entrances, they would share out the mushroom’s gifts with those within.

The Amanita muscaria mushrooms are often dried before ceremonial consumption, reducing the mushroom’s toxicity while increasing its potency. Families would often hang them in socks around the fireplace to dry, ready to be shared on the morning of the solstice.

In the initiations of shamans in Buryatia, a tree will actually be erected inside the yurt. Sometimes the shaman literally climbs the tree, other times drumming at the base and only ascending with his spiritual being. As the shaman ascends the tree in his ecstatic state, he describes his journey to the upper world. To journey to this upper world requires the ability to fly, so the shamans often change themselves into birds or ride upon a flying deer or horse to make the journey. The magic flight of Santa Claus through the midwinter night sky is a superb expression of the basis of all shamanism – ecstasy, or the flight of the spirit.

In Popular Culture

In Victorian times travelers returned with intriguing tales of the use of fly agaric by people in Siberia, Lapland, and other areas in the northern latitudes. One of the first was reported by the mycologist Mordecai Cooke, who mentioned the recycling of urine rich in muscimol in his A Plain and Easy Account of British Fungi (1862). Patrick Harding of Sheffield University points out that Cooke was a friend of Charles Dodgson (Lewis Carroll), the author of the fantastic children’s story Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland (1865). “Almost certainly, this is the source of the episode in Alice where she eats the mushroom, where one side makes her grow very tall and the other very small,” Harding says. “This inability to judge size—macropsia—is one of the effects of fly agaric.” It is also interesting to note that, in central Europe, the fly agaric has been adopted as the symbol of chimney sweeps.

Controversy

There are some historians, such as Ronald Hutton, who refute the connection between the amanita muscaria and the legend of Santa Claus. “The Santa Claus we know and love was invented by a New Yorker, it really is true,” Hutton says. “It was the work of Clement Clarke Moore, in New York City in 1822, who suddenly turned a medieval saint into a flying, reindeer-driving spirit of the Northern midwinter.” Moore brought that beloved Santa Claus to life in his poem, “A Visit from St. Nicholas,” otherwise known as “The Night Before Christmas.”

From Wikipedia, “Hutton claims that reindeer spirits did not appear in Siberian mythology, shamans did not travel by sleigh, nor did they wear red and white or climb out of smoke holes in yurt roofs. Finally, American awareness of Siberian shamanism postdated the appearance of much of the folklore around Santa.”

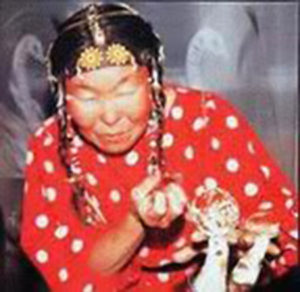

But reindeer were very important in Siberian mythology, they even put antlers on their headdresses to symbolize the protective spirit of the reindeer. The Chuchki and Koryaks of Siberia do train reindeer to pull them on sledges. Hutton is right that shamans do not exclusively wear red and white, but this picture of a Kamchatkan (Northeast Siberian) shamaness with fly-agaric mushrooms proves this is a real phenomena. (Photo by Emanuel Salzman).

Whether or not the smoke hole was used as a second entrance to the yurt, the connection between the shaman and the smoke hole of the yurt is well documented. The dwelling of the shaman was easy to recognize due to the top of the tree placed inside poking through the smoke hole. During ceremony, the shaman would climb the tree to shamanize, calling deities and ancestor spirits from the top of the yurt.

Hutton’s final claim that awareness of Siberian shamanism came after the evolution of our Santa Claus is irrelevant. The date of the 25th of December, for example, is pagan in origin although for most of the last two thousand years most Christians were not aware of that fact. Traditions and ideas regularly evolve without public knowledge. And there’s always the possibility that Moore was not aware of this mythology but was pulling inspiration from the collective consciousness.

Either way, there’s some powerful synchronicity here. But don’t take my word for it. I leave you in the capable hands of the BBC. Merry Christmas!

♥ ♥ ♥